Amanda Mull examines why.

Because consumer identities are constructed by external forces, [historian Susan Strasser, the author of Satisfaction Guaranteed: The Making of the American Mass Market] said, they are uniquely vulnerable, and the people who hold them are uniquely insecure. If your self-perception is predicated on how you spend your money, then you have to keep spending it, especially if your overall class status has become precarious, as it has for millions of middle-class people in the past few decades. At some point, one of those transactions will be acutely unsatisfying. Those instances, instead of being minor and routine inconveniences, destabilize something inside people, Strasser told me. Although Americans at pretty much every income level have now been socialized into this behavior by the pervasiveness of consumer life, its breakdown can be a reminder of the psychological trap of middle-classness, the one that service-worker deference to consumers allows people to forget temporarily: You know, deep down, that you’re not as rich or as powerful as you’ve been made to feel by the people who want something from you. Your station in life is much more similar to that of the cashier or the receptionist than to the person who signs their paychecks.

There are endless ways to make sense of the situation America is in now, in which new horror stories from retail hell make national news every few days, and stores and restaurants all over the country complain that no one wants to work for them. Perhaps the most obvious one is simply how damaging this whole arrangement is for service workers. Although underpaid, poorly treated service workers certainly exist around the world, American expectations on their behavior are particularly extreme and widespread, according to Nancy Wong, a consumer psychologist and the chair of the consumer-science department at the University of Wisconsin. “Business is at fault here,” Wong told me. “This whole industry has profited from exploitation of a class of workers that clearly should not be sustainable.”

When I was a kid, I read Robert Heinlein's novel Friday, which contained this observation: “Sick cultures show a complex of symptoms such as you have named...but a dying culture invariably exhibits personal rudeness. Bad manners. Lack of consideration for others in minor matters. A loss of politeness, of gentle manners, is more significant than is a riot.”

Fifty years ago today, George Harrison and Ravi Shankar put on the Concert for Bangladesh at Madison Square Garden:

It was the first major charity concert of its kind — the Concert for Bangladesh. In that corner of South Asia, civil war, cyclone and floods had created a humanitarian disaster.

"There are six million displaced Bengalis, most of them suffering from malnutrition, cholera and also other diseases that are the result of living under the most dehumanizing conditions," former All Things Considered host Mike Waters reported in July of 1971.

The situation was deeply personal for Indian musician Ravi Shankar, a sitar virtuoso, whose family came from the region. So, Shankar reached out to a close friend, former Beatle George Harrison.

He marveled at the astonishing roster Harrison was able to attract. "You have a Beatle — two Beatles in fact — that you have Ringo Starr as well. You have Bob Dylan," Thomson says. "None of these people had played live particularly much in the preceding years. So, that was an event in itself. You have a stellar backing band, people like Eric Clapton." Including, of course, Shankar on the sitar.

What they did end up making went to UNICEF. That weekend alone raised around $240,000. Millions more came later, as a result of the subsequent album and movie, all with the goal of helping refugees.

And exactly ten years later, MTV was born. (And I still have a crush on Martha Quinn.)

Just a couple of articles that caught my interest this morning:

Finally, today is the 65th anniversary of the collision between the Stockholm and the Andrea Doria off the coast of Nantucket in which 1,646 people were saved before the Doria sank.

I know, two days in a row I can't be arsed to write a real blog post. Sometimes I have actual work to do, y'know?

Finally, as I've gone through my CD collection in the order I bought them, I occasionally encounter something that has not aged well. Today I came across Julie Brown's "The Homecoming Queen's Got a Gun," which...just, no. Not in this century.

Having finished Hard Times, I started a new book last night, and realized right away it will take me a year to read. The book, Shit Went Down (On This Day in History) by James Fell relates an historical event for each day of the year. The recommendation came from John Scalzi's blog. I have about 60 recommendations from Scalzi's blog now, and someday I might read a fraction of those books.

Fell's book reminds me that on this day in 1925, a jury in Dayton, Tennessee, convicted John Scopes of teaching human evolution in a state-funded school. Despite the wonderful things that have come out of Tennessee, the state's constant competition with neighboring Mississippi and Alabama for the "stupidest legislation of the decade" award always entertains. My friends from the state assure me that smart people actually do live there, but their protestations have less of a persuasive effect given they left Tennessee at the first opportunity.

In any event, I really need to carve out more time for reading. Come on, UK, open up to vaccinated visitors already! I need the airplane time.

I've just yesterday finished Charles Dickens' Hard Times, his shortest and possibly most-Dickensian novel. I'm still thinking about it, and I plan to discuss it with someone who has studied it in depth later this week. I have to say, though, for a 175-year-old novel, it has a lot of relevance for our situation today.

It's by turns funny, enraging, and strange. On a few occasions I had to remind myself that Dickens himself invented a particular plot device that today has become cliché, which I also found funny, enraging, and strange. Characters with names like Gradgrind, Bounderby, and Jupe populate the smoke-covered Coketown (probably an expy for Preston, Lancashire). Writers since Dickens have parodied the (already satirical) upper-class twit and humbug-spewing mill owner so much that reading them in the original Dickens caused some mental frisson.

Dickens also spends a good bit of ink criticizing "political economics" in the novel, as did a German contemporary of his, whose deeper analysis of the same subject 13 years later informed political philosophy for 120 years.

It's going to sit with me for a while. I understand that Tom Baker played Bounderby in a BBC Radio adaptation in 1998; I may have to subscribe to Audible for that.

...that I left a medium-sized consulting firm based here in Chicago. The firm itself doesn't really matter. I left because I couldn't tolerate commuting to Houston every week to work on a project for a now-infamous energy trading firm there. No one seemed too interested in me saying the client had serious problems, and that the project, if it worked, would break all kinds of anti-trust laws. By mid-October the client proved me right when its house of cards collapsed.

I have some recollections of the summer of 2001, but of course things changed quickly, right after I started a new gig for a cool start-up on the eastern edge of Ukrainian Village. My first day was the Monday after Labor Day, the 10th.

What a strange year that was. Good thing everyone has calmed down since then.

According to an upcoming book by Washington Post reporters Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker, Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley seriously worried about the XPOTUS attempting an autogolpe in January:

Milley described “a stomach-churning” feeling as he listened to Trump’s untrue complaints of election fraud, drawing a comparison to the 1933 attack on Germany’s parliament building that Hitler used as a pretext to establish a Nazi dictatorship.

In December, with rumors circulating that the president was preparing to fire then-CIA Director Gina Haspel and replace her with Trump loyalist Kash Patel, Milley sought to intervene, the book says. He confronted White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows at the annual Army-Navy football game, which Trump and other high-profile guests attended.

“What the hell is going on here?” Milley asked Meadows, according to the book’s account. “What are you guys doing?”

When Meadows responded, “Don’t worry about it,” Milley shot him a warning: “Just be careful.”

Greg Sargent warns we need immediate reforms to make sure we never get that close to a coup again:

Milley’s general overarching fear was absolutely correct: Trump and key strains of the movement behind him were unquestionably willing to resort to potentially illegal and violent means to thwart the transfer of power from Trump to the legitimately elected new government. They actually did attempt this.

On certification of federal elections, Congress could set standards for states that streamline the certification process to take pressure off low-level election boards, and place ultimate control of certification in the hands of state judicial actors who are ostensibly nonpartisan. That would make it harder to corrupt certification.

On state legislatures sending rogue electors, Congress could revise the Electoral Count Act. Ideas include setting higher evidentiary standards for objections to electors, making the threshold for objecting higher than one senator and representative, and requiring two-thirds of Congress to sustain an objection.

This could avert a 2024 scenario in which a GOP legislature in one deciding state buckles this time under pressure to send rogue electors, and a GOP-controlled chamber in Congress counts them, creating a severe crisis at best and a stolen election at worst.

Whatever reforms we choose, the basic guiding idea here should be this. We don’t just want to make it harder to corrupt these processes, but also to reduce the incentive to pressure officials at all these levels to do so, since it would be less likely to succeed.

Milley’s fear of a Trump military coup was not borne out. But this shouldn’t lead us to congratulate ourselves over Trump’s incompetence or the virtues of individual players. It should add to our urgency to act.

Scary stuff. And the Republican Party continues to push towards minority rule, having given up on democracy itself. So yes, we need to fix this, to the extent possible.

CityLab's Feargus O'Sullivan riffs on an Instagram account that celebrates Scooby-Doo's Victorian backdrops:

It should come as no surprise that creaking mansard roofs, vaulted dungeons and abandoned one-horse towns occur so often as settings. Americans have been identifying the Victorian with the macabre for more than 100 years. It still seems not completely coincidental that these particular backdrops were so often used for a show in its heyday in the late 1960s and the 1970s.

This, after all, is a period when America’s Victorian architecture lay on a major fault line. Long decaying as wealthier residents moved to the suburbs, America’s many Victorian neighborhoods fell prey to demolition during this period as urban renewal projects smashed through buildings that were often seen as musty, decrepit hangovers from a poorer, miserably car-less past.

San Francisco’s Fillmore District, for example, was substantially redeveloped, scattering its mainly African American residents to the East Bay, while the now celebrated Victorian district of Old Louisville saw over 600 buildings demolished between 1965 and 1971 alone.

Indeed, the show sometimes tackles these issues directly. The classic Scooby-Doo villain is a developer or greedy landowner, scaring people away from their property by dressing as a ghost or monster, only to be unmasked and confess everything to the band of “pesky kids” just before each episode’s final curtain. Occasionally, even urban renewal itself crops up. In one episode a developer constructing new buildings in Seattle is also secretly plundering treasures from the subterranean street network built in the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1889.

Down the street from me, a 6-bedroom house built in 1897 just sold for $412,500—less than half its estimated value, and probably closer to a third of what it might fetch once its restoration finishes next year. It went for $28,500 in 1979, which works out to about $110,000 today, during the worst period of urban decay in Uptown. Other gorgeous houses and apartments from the 1890s through 1920s in Chicago barely survived the 1970s, sometimes only because no one wanted to invest in the neighborhoods.

I've written about this phenomenon before, of course.

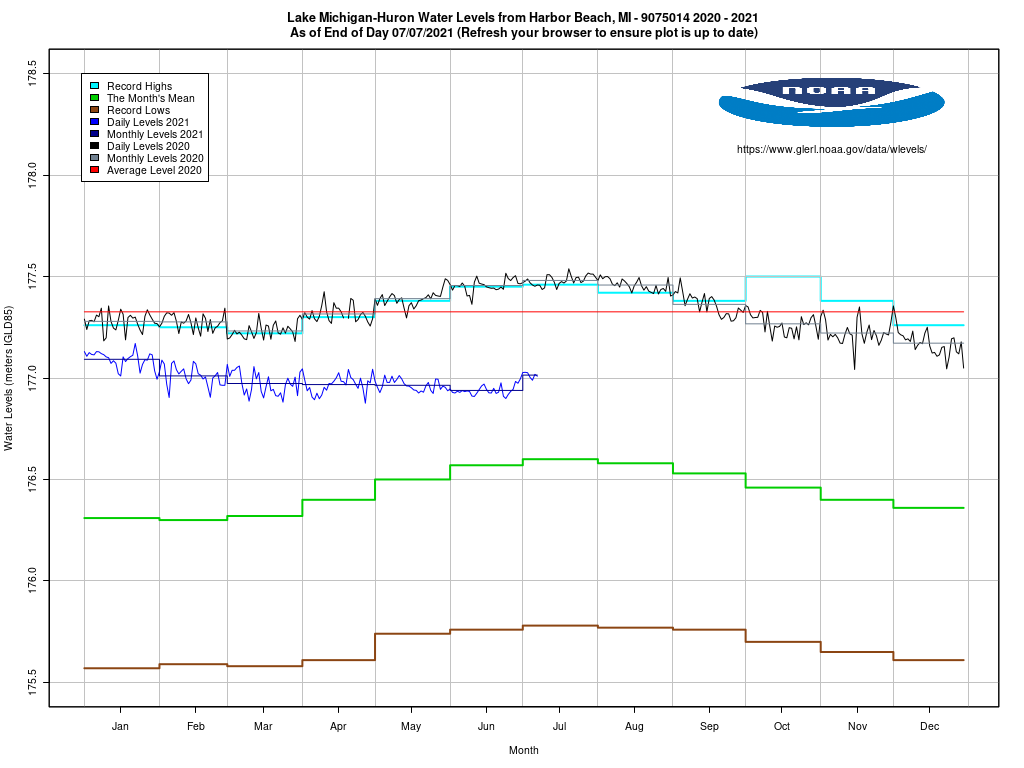

Dan Egan, author of The Death and Life of the Great Lakes (which I read last November while staring out at one of them), explains in yesterday's New York Times how climate change will cause problems here in Chicago:

[T]he same waters that gave life to the city threaten it today, because Chicago is built on a shaky prospect — the idea that the swamp that was drained will stay tamed and that Lake Michigan’s shoreline will remain in essentially the same place it’s been for the past 300 years.

Lake Michigan’s water level has historically risen or fallen by just a matter of inches over the course of a year, swelling in summer following the spring snowmelt and falling off in winter. Bigger oscillations, a few feet up or down from the average, also took place in slow, almost rhythmic cycles unfolding over the course of decades.

No more.

In 2013, Lake Michigan plunged to a low not seen since record-keeping began in the mid-1800s, wreaking havoc across the Midwest. Marina docks became useless catwalks. Freighter captains couldn’t fully load their ships. And fears grew that the lake would drop so low it would no longer be able to feed the Chicago River, the defining waterway that snakes through the heart of the city.

That fear was short-lived. Just a year later, in 2014, the lake started climbing at a stunning rate, ultimately setting a record summertime high in 2020 before drought took hold and water levels started plunging again.

Egan explains in detail what that means for us, culminating in the harrowing near-disaster of 17 May 2020, when record rains combined with a record-high lake to make draining downtown Chicago almost impossible.

I should note that, after falling for 11 consecutive months, the lake has started to rise again (blue line), and we haven't even gotten down to our long-term average (green line):

I've said for decades that Chicago will fare better than most places, but that doesn't mean we'll have it easy. Nowhere will.