Today's Blogging A-to-Z challenge post will discuss a form of music that, sadly, doesn't turn up much anymore. I say "sadly" because the fugue is one of the most intricate and difficult-to-write musical forms, but also one of the most satisfying when done well—and no one did it better than old J.S. Bach.

Today's Blogging A-to-Z challenge post will discuss a form of music that, sadly, doesn't turn up much anymore. I say "sadly" because the fugue is one of the most intricate and difficult-to-write musical forms, but also one of the most satisfying when done well—and no one did it better than old J.S. Bach.

At its most basic, a fugue takes a short musical subject and tosses it around two or more voices in counterpoint; that is, each musical line (voice) stands on its own as a melody, but the melodies combine to form a more complex whole.

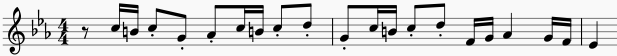

Take this two-bar subject:

Now listen to what Bach does with it:

Let's dig into what actually happens in there.

First we hear the two-bar theme, followed the second voice with the same two-bar theme starting on the dominant note. But notice the first voice keeps going, and then the two voices play off each other with bits of the theme. Then a few bars later, the third voice enters on the tonic again, and we're off to the races.

The fugue returns to the theme several times in each of the voices: in the relative major at bar 11, then at the relative major's own dominant at 13, before returning to C minor at 21. Between these Bach inserts episodes, where the voices interact without returning to the theme. Or so the German would have you believe! Because it's there, sometimes in pieces, at half-speed, upside down, and backwards.

Finally the lowest voice enters boldly with the theme for the last time, after which it hangs out on a tonic pedal while the upper two voices let the theme become the final cadence of the fugue. (Bonus points if you noticed the German sixth in bar 30.)

Bach wrote 48 fugues in his two-volume Well Tempered Clavier, which was sort of a product launch for something so technical I'm coming back to it on the 26th. He also wrote The Art of the Fugue, which is exactly what it says on the tin, and countless other fugues as parts of longer works. Mozart, who loved Bach's music more than almost everyone alive in the 1780s, tried his hand at a few. One of his best is in the 4th movement of the Solemn Vespers of the Confessor, K339, "Laudate pueri Dominum" (Psalm 113, "Blessed be the servants of the Lord", complete with yet another cool example of a German sixth in the "amen" bit at the end).

For really hard-core fugueing, check out Morzart's massive choral fugue in the "Cum Sancto Spiritu" movement of his Mass in c-minor, K427, or Handel's "Amen" fugue that ends Messiah. (And, of course, you must hear the Apollo Chorus perform this fugue from memory next December.)

Note that A-to-Z posts run Monday through Saturday, so come back Monday for the G post. Or check back over the weekend for my usual politics, weather, and the dog.