Welcome to the Daily Parker's first entry in this year's Blogging A-to-Z challenge on the theme "Basic Music Theory." Today: A is for A.

Welcome to the Daily Parker's first entry in this year's Blogging A-to-Z challenge on the theme "Basic Music Theory." Today: A is for A.

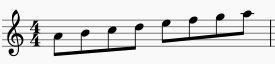

In Western music, A represents the note that all other notes are based upon. The other notes in Western music are B, C, D, E, F, and G. Putting all those notes in sequence is called a scale:

That scale is called "A natural minor," and sounds like this. The first note in the scale is A; in the attached midi file, and generally in music today, it has a frequency of 440 Hz.

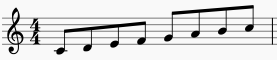

The minor scale feels a little sad, or melancholy, to most people. You're probably more familiar with the major scale. We can create a major scale most easily by starting on a different note. If we start on C, we get a completely different feeling:

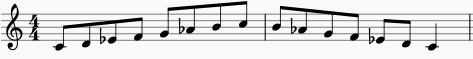

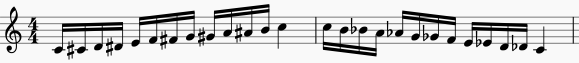

We're not limited just to the plain notes on the scale, either. We can add accidentals, which tell the musician to increase (sharp) the frequency of the sound or decrease (flat) it. By adding two flats to the C-major scale, we can turn it into the C harmonic minor scale:

The little "b"-like symbols on the third and sixth notes of the scale indicate that the E and the A are flat. The B is still natural (neither sharp nor flat), giving the scale a slightly exotic feeling.

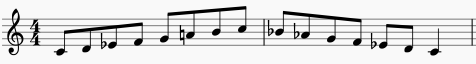

There is one more ordinary scale, called melodic minor. This has one flattened note going up (in this case, E-flat), and uses the natural minor going down. Note that the half-hash symbol before the A in the first bar says that the note is exactly what it says on the tin, without sharp or flat modification. Here's the C melodic minor scale:

Western music has these four scales (major, natural minor, harmonic minor, and melodic minor) for about 500 years. But other scales have become more popular in the late 20th and early 21st century. Popular music has even gone back to "modes," which come from ancient Greek music through the early middle ages. But that's out of the scope of this year's A-to-Z challenge.

Finally, there is the chromatic scale, which includes every note possible (and every note on a piano keyboard):

Notice that going up we sharp the notes and coming down we flat them, showing all of the enharmonic equivalents (D-flat is the enharmonic equivalent of C-sharp because they occupy the same place in the chromatic scale)*.

* If you get technical, they're not actually the same notes, but we'll come back to that towards the end of the month.

Also, as a handy guide for future posts, here are the names of the diatonic notes on the scale:

| # |

Name |

Major |

Minor |

| 1 |

tonic |

C - I |

A - i |

| 2 |

supertonic |

D - ii |

B - ii |

| 3 |

mediant |

E - iii |

C - III |

| 4 |

subdominant |

F - IV |

D - iv |

| 5 |

dominant |

G - V |

E - v |

| 6 |

submediant |

A - vi |

F - VI |

| 7 |

leading tone |

B - vii |

G - VII |

This is a gross oversimplification, only so you get the gist. Just understand the vocabulary: for example, that E is the mediant of C and the dominant of A. If you start on a different note, it still works the same way: C is the dominant of F; A sharp is the submediant of C sharp and the dominant of D sharp.

We'll get deeper into these concepts as the month goes on.