Writing in Forbes, psychologist Todd Essig says it's perfectly plausible that Brett Kavanaugh has no recollection of what to Christine Blasey Ford was a life-changing event:

It is distinctly possible that his lack of memory is not because it never happened but because he really has no recollection of it taking place. He never encoded the event. Therefore, he cannot remember something he never noticed, even though it proved to be life-altering for someone else.

As Dr. Richard Friedman wrote this week, an attack usually triggers intense emotions and stress hormones that facilitate encoding memories. That is why “you can easily forget where you put your smartphone or what you had for dinner last night or last year. But you will almost never forget who raped you, whether it happened yesterday — or 36 years ago.”

Of course, this doesn’t let [Kavanaugh] off the hook for what he did or at all suggest he either has or doesn’t have the qualities one needs in a Supreme Court Justice. It’s just that he may not be lying about what he recalls. It also doesn’t excuse the self-serving way he transformed the absence of memory into the presence of certainty that something didn’t happen. A judge should know better than to rest his career on such a logical incongruity.

For another take on this phenomenon, check out Deborah Copaken's moving essay in The Atlantic, "My Rapist Apologized."

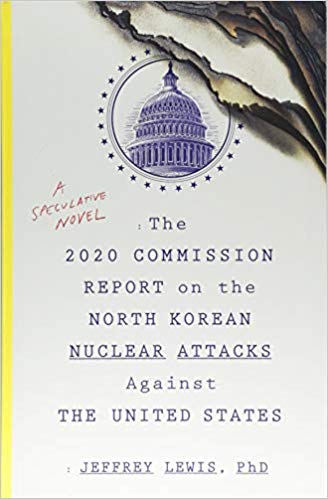

Yesterday I finished Dr. Jeffrey Lewis's speculative novel, The 2020 Commission Report on the North Korean Nuclear Attacks Against the United States. Why scary? Because Lewis lays out, clearly and without hyperbole, a plausible scenario for what could be the most destructive conflict in human history.

In conjunction with Bob Woodward's Fear and the soon-to-be released The Apprentice, it's even scarier—and no less plausible.

Spend $15 and read this book.

Last week, The Economist celebrated its 175th anniversary with a call for renewing liberalism:

Liberalism made the modern world, but the modern world is turning against it. Europe and America are in the throes of a popular rebellion against liberal elites, who are seen as self-serving and unable, or unwilling, to solve the problems of ordinary people. Elsewhere a 25-year shift towards freedom and open markets has gone into reverse, even as China, soon to be the world’s largest economy, shows that dictatorships can thrive.

For The Economist this is profoundly worrying. We were created 175 years ago to campaign for liberalism—not the leftish “progressivism” of American university campuses or the rightish “ultraliberalism” conjured up by the French commentariat, but a universal commitment to individual dignity, open markets, limited government and a faith in human progress brought about by debate and reform.

Liberals have forgotten that their founding idea is civic respect for all. Our centenary editorial, written in 1943 as the war against fascism raged, set this out in two complementary principles. The first is freedom: that it is “not only just and wise but also profitable…to let people do what they want.” The second is the common interest: that “human society…can be an association for the welfare of all.”

Today’s liberal meritocracy sits uncomfortably with that inclusive definition of freedom. The ruling class live in a bubble. They go to the same colleges, marry each other, live in the same streets and work in the same offices. Remote from power, most people are expected to be content with growing material prosperity instead. Yet, amid stagnating productivity and the fiscal austerity that followed the financial crisis of 2008, even this promise has often been broken.

It's hard to read this leader and its accompanying essay without cheering. I only hope it can gain some traction.

The Washington Post has a must-read feature today about the sexual assault of 16-year-old Amber Wyatt in 2006—and how her Texas high school turned against her:

The rumor — at least initially, and certainly in the soccer player’s initial account to Aven — wasn’t that Wyatt consented to sex with the two boys, but that they never had sex at all. Yet the tone of murmurs around the school indicated that students believed the exact opposite: that Wyatt, perhaps intoxicated, had agreed to sex and then regretted it, and that, in accusing the boys of rape, caused trouble not only for herself but also for her classmates at Martin. Aven, in his statement to police, said he thought, despite the soccer player’s denials, that some consensual sexual encounter took place in the shed that night. Meanwhile, at the school, an internal investigation quickly began into students’ alcohol use, which resulted in athletes from four different sports being removed from their extracurricular activities for six weeks.

Wyatt became the bull’s eye of an angry backlash. As Liz Gebhardt, a close friend of Wyatt’s who remained by her side throughout the tumultuous period that followed, recalled: “Everyone started blaming [Wyatt] because she said something, and if she would have kept her mouth shut then nothing would have ever happened.” With 3,350 students, it was hard to contain the spread of malicious recrimination and even harder to maintain a sense of proportion.

Kids hurled insults at Wyatt in the halls and casually chatted about the news in class. Many of her former friends would no longer associate with her. Wyatt says she received threats and slurs by text messages, people telling her to kill herself, saying she got what was coming to her. Wyatt’s friendships with her former cheerleading pals grew brittle and strained. “Maybe it was me,” she speculated in 2015. “I mean, I totally changed.”

One night in September, text and MySpace messages began circulating among Martin teens who wanted to show support for the accused by writing “FAITH” on their cars. The lurid acronym — “f--- Amber in the head” — began appearing on rear windows the following morning, metastasizing as quickly as the rumors had. Even Arthur Aven wrote “FAITH” on his car.

It's as much an indictment of her town's justice system as much as her classmates. Wyatt has recovered, but it took a decade to get her life on track. The people she alleged had raped her had no consequences.

Lots of stuff crossed my inbox this morning:

Back to my wonderful, happy software debugging adventure.

Freddie Oversteegen, who died September 5th just one day shy of her 93rd birthday, fought in the Dutch Resistance as a teenager:

When she rode her bicycle down the streets of Haarlem in North Holland, firearms hidden in a basket, Nazi officials rarely stopped to question her. When she walked through the woods, serving as a lookout or seductively leading her SS target to a secluded place, there was little indication that she carried a handgun and was preparing an execution.

Yet Freddie Oversteegen and her sister Truus, two years her senior, were rare exceptions — a pair of teenage women who took up arms against Nazi occupiers and Dutch “traitors” on the outskirts of Amsterdam. With Hannie Schaft, a onetime law student with fiery red hair, they sabotaged bridges and rail lines with dynamite, shot Nazis while riding their bikes, and donned disguises to smuggle Jewish children across the country and sometimes out of concentration camps.

In perhaps their most daring act, they seduced their targets in taverns or bars, asked if they wanted to “go for a stroll” in the forest — and “liquidated” them, as Ms. Oversteegen put it, with a pull of the trigger.

The whole obituary is worth a read.

President Trump has complained about how much Robert Mueller's investigation has cost the government. After the plea deal reached Friday with Paul Manafort, that should no longer be a problem:

If we assume the same cost-per-day for the investigation that was reported through March of this year, the probe has so far cost the government about $26 million.

[P]art of the plea agreement reached between Mueller and former Trump campaign chairman Paul Manafort includes forfeiture of certain property to the government. While it’s not clear how much value will be extracted from that forfeiture, there’s reason to think that it could more than pay for what Mueller has incurred so far.

The combined value of [Manafort's] properties, according to estimates at Zillow.com and assigning the 2006 sale price to his Trump Tower property, is about $22.2 million. If those were sold at the values identified above and the money returned to the government, that alone nearly covers our estimated costs of the investigation to date.

The government’s seizures from Manafort could be worth about $42 million, including the upper estimates of just the properties, Federal Savings Bank loan and insurance policies. And that doesn’t include the other accounts, which might contain some portion of the $30 million that Wheeler points to as having been identified by the government as ill-gotten gains. That’s enough to pay for the Mueller probe for some time to come.

Somehow, though, I don't thing Trump is as much concerned about the money as he is about what Manafort has told Mueller's team. That, I suspect, is his real concern.

VW will stop making the original People's Car later this year:

The streets of American cities were once carpeted in Bugs. From 1968 to 1973, more than a million were sold every year. In 1972, when it passed the 15 million mark, the Bug overtook the Ford Model T as the best-selling vehicle on the planet.

Yesterday, the German automaker announced that it would be killing the Beetle brand for the 2019 model year, news that surprised zero industry observers—these plans have been known for years—but still generated an involuntary spasm of nostalgia. Volkswagen, after all, has been making Beetles of one kind or another since the 1930s.

The Bug, like the many other, even tinier city cars that emerged from Europe after World War II, may have been similarly austere, but its heart was light, its face was friendly and round, and it was made for a youthful and urban world. You could stuff a family of five in there, or 18 college kids. You could park it anywhere. If it broke, you could pull the engine out and fix it on your kitchen table. For millions of young people—students, moms, working parents—the cheap, gas-sipping VW was your ticket to selfhood. Ford may have built the automobile age, but the Beetle conquered the city.

For the record, I was once one of 13 high-schoolers in an original VW Beetle.

Before diving back into one of the most abominable wrecks of a software application I've seen in years, I've lined up some stuff to read when I need to take a break:

OK. Firing up Visual Studio, reaching for the Valium...

While trying to debug an ancient application that has been the undoing of just about everyone on my team, I've put these articles aside for later:

Back to the mouldering pile of fetid dingo kidneys that is this application...