Today's Blogging A-to-Z challenge post explains how musicians keep time.

Today's Blogging A-to-Z challenge post explains how musicians keep time.

Through all the examples I've posted this month, you may have noticed that a note's stem has a relationship to how long the note sounds. They do. Starting with a whole note (open, with no stem), each change to the stem reduces the length of the note by half. This also works when you start with a whole rest, except a rest means "don't do anything here." Example:

(In the UK, those notes are called whole, half, quarter, quaver, semiquaver, hemisemiquaver, and hemisemidemiquaver. Don't ask me why.)

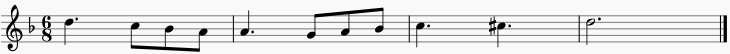

You can also add a dot after a note, which increases the length by 50%. The dotted quarter notes in this example are the same as three 8th notes:

On the same subject, let me draw your attention to the numbers (and sometimes letters) that follow the key signature in a staff. That guy, called the time signature, tells performers how to count.

The most common time signature is 4/4. That means there are 4 beats in each measure (the top number) and the quarter note gets one beat. It's so common that it can also be represented by the letter C, as in the top example above. Sometimes you'll see a C with a line through it. This is called cut time, or 2/2, in which there are two half-note beats per measure.

The second example above shows 6/8 time, in which there are six eighth notes to each measure. Typically musicians count 6/8 as two beats per measure, with the dotted quarter getting the beat, so it feels like a march.

The time signature 3/4 has the same number of eighth notes per measure, but since the quarter note gets the count, there are three quarter-note beats per measure. This is the time signature for waltzes.

Almost any combination of beats and notes can form a time signature. I've seen 7/4, 3/16, 1/1, 9/32...literally anything as long as the bottom number is divisible by 2 (or is 1). That said, the most common time signatures by far are 4/4, 6/8, 3/4, and 2/2.

And here, for your listening enjoyment, is a piece that flouts all the rules and somehow works—as humor: